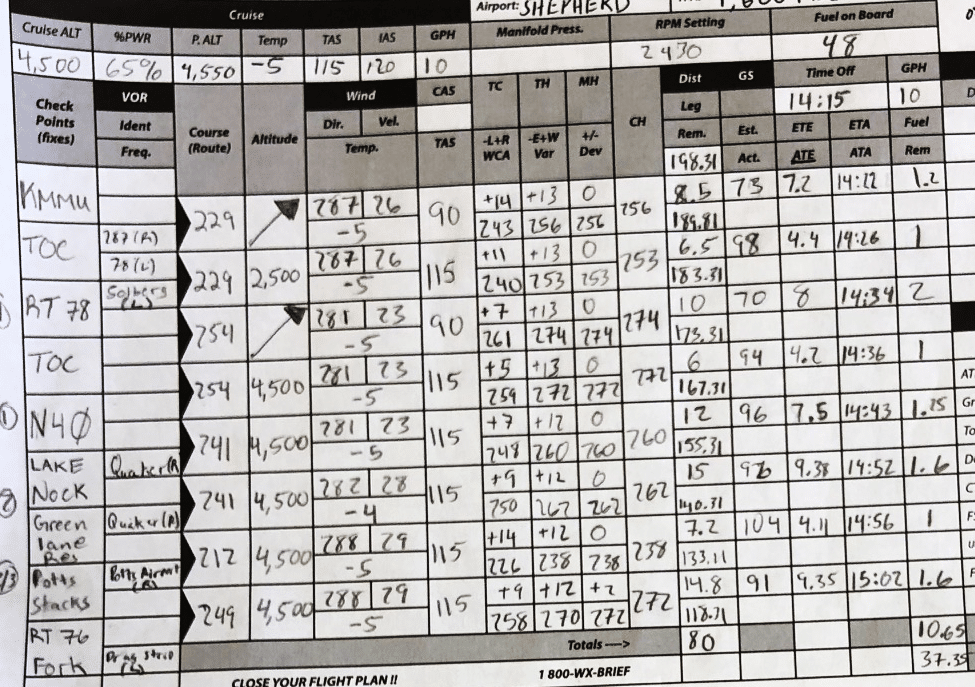

Having participated in many aviation discussions both online and in person over the last two decades of my flying life, I’ve noticed a conversation which keeps popping up. It has to do with flight planning — both from a “checkride perspective” and then “what you do in the real world.” A common refrain I hear is: once a pilot passes his or her private pilot checkride, dispense with the manual calculations and rely on a flight planning application to perform them instead.

Indeed, many — probably most — pilots do not continue creating VFR navigation logs by hand after earning their private pilot certificate. There are many tools which seem to automate the process perfectly well, after all; popular EFB “apps” such as ForeFlight and Garmin Pilot offer “one tap” functionality to build an accurate flight plan.

First, let me put you at ease by saying “that’s okay!” I use ForeFlight or Fltplan.com to plan my own flights in my personal aircraft. For my professional flying I rely on advanced tools from Collins Aerospace to assist with flight planning in super-midsize to large cabin business jets. So do most professional pilots.

But it’s going to take a little bit more than pushing (or tapping) a button to get it done right. There’s no “Easy Button” for flight planning.

Precision matters… accuracy matters

The issue then becomes “just how precise and accurate does my flight plan need to be?” To which I would answer, “As precise and accurate as possible — always!” One would assume a flight plan created on an EFB would be “precisely accurate,” but is it, really?

There’s no one black/white, right/wrong answer to this question. But we do have some guidance from our friends at the FAA, and in my experience it is

- the most commonly “violated” regulation in 14 CFR Part 91, and

- among the most important regulations in 14 CFR Part 91 to actually know and adhere to.

I am referring to 14 CFR §91.103, “Preflight action.” (Click to expand.)

§91.103 Preflight action.

Each pilot in command shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all available information concerning that flight. This information must include—

(a) For a flight under IFR or a flight not in the vicinity of an airport, weather reports and forecasts, fuel requirements, alternatives available if the planned flight cannot be completed, and any known traffic delays of which the pilot in command has been advised by ATC;

(b) For any flight, runway lengths at airports of intended use, and the following takeoff and landing distance information:

(1) For civil aircraft for which an approved Airplane or Rotorcraft Flight Manual containing takeoff and landing distance data is required, the takeoff and landing distance data contained therein; and

(2) For civil aircraft other than those specified in paragraph (b)(1) of this section, other reliable information appropriate to the aircraft, relating to aircraft performance under expected values of airport elevation and runway slope, aircraft gross weight, and wind and temperature.

I said “in my experience.” I am referring to aircraft accidents and my involvement with their resolution — both as a consulting expert for high-profile business jet accidents and in my role providing Remedial Training to airmen on behalf of the Teterboro FSDO. I’d feel quite comfortable going on record to say failure to adhere to §91.103 plays a role in every single one of them.

With that said, let’s review what this regulation actually states. The essence of §91.103 can be found in its very first sentence. The FAA is placing an immense onus on the pilot in command. The underline was added by me:

Each pilot in command shall, before beginning a flight, become familiar with all available information concerning that flight.

14 CFR §91.103

This makes the remainder of the regulation a sort of regulatory footnote, because “all available information” means exactly that!

But there’s value to seeing some high level items here; if you’re leaving the airport traffic pattern or flying IFR, you need to be familiar with weather reports and forecasts, alternatives, known traffic delays; and in case you happen to just be sticking with VFR pattern work today, you still must know runway lengths and understand takeoff and landing distance data if that data has been published in the Airplane or Rotorcraft Flight Manual. For airplanes that don’t publish this data (J-3 Cub, anyone?) the FAA still insists that the pilot reference “other reliable information” relating to the aircraft’s performance for the conditions of the day.

The common memory aid here which I see used in airman certification is “W-KRAFT.” That’s the rote answer to the checkride question.

Weather.

“(a) For a flight under IFR or a flight not in the vicinity of an airport, weather reports and forecasts… “

Known Traffic Delays.

“… known traffic delays of which the pilot in command has been advised by ATC… “

Runway Lengths.

“For any flight, runway lengths at airports of intended use… “

Alternatives.

“… alternatives available if the planned flight cannot be completed… “

Fuel requirements.

“… fuel requirements… “

Takeoff and Landing Distance Information.

“… the following takeoff and landing distance information:

(1) For civil aircraft for which an approved Airplane or Rotorcraft Flight Manual containing takeoff and landing distance data is required, the takeoff and landing distance data contained therein; and

(2) For civil aircraft other than those specified in paragraph (b)(1) of this section, other reliable information appropriate to the aircraft, relating to aircraft performance under expected values of airport elevation and runway slope, aircraft gross weight, and wind and temperature. “

On the next page, we’ll look at an example of how failing to adhere to this regulation can cause problems on a practical test… followed by a tragic accident with similar components.