But the Accident…

Back to N452DA. We should all hesitate to criticize pilots or crews for the mistakes they made. After all, we are all capable of substandard performance. Rather, it’s more productive to go one, two, or three levels deeper and look at the system we’ve made in aviation which can lead pilots into thinking the decisions which led to this accident are acceptable at the time. This is called performing a RCA, or Root Cause Analysis.

At its deepest level, it could be said that the root cause for this accident had to do with the organization which hired and paired the pilots for this flight. The captain, while reasonably experienced at 6,900 total hours and 353 PIC in the LR-JET, had some red flags in his training documentation and work background. The SIC, at 1,170 total hours was inexperienced and had “struggled” in simulator training. So inexperienced and so challenged in his current role that the company rated him “SIC-0” on a 0-4 scale. This rating only allowed him to perform SIC duties as PM (or Pilot Monitoring.) Yet the PIC decided to “instruct” the SIC on the fatal flight, despite the SIC’s periodic, but weak, protests.

What we’re starting to see in business aviation or charter ops is that fatal accidents, when they happen, aren’t usually caused by equipment failure or minor crewmember oversights. Rather, the crew typically demonstrates an extreme deviance from accepted practices, standards, and regulations. The 2016 crash of a Hawker 700A in Akron, Ohio shared many similarities to this one; poor crew pairing, red flags in the training files, operating contrary to company policy and a PIC “instructing” a challenged SIC during the approach are but a few examples. Again, RCA points to an organizational challenge which is invariably linked with a weak safety culture.

It seems that the fatal accidents we’ve seen in recent years in business aviation and Part 135 tend to represent operations who failed to go “all in” with their safety culture. That’s just one man’s opinion, but I can assure you I’m not the only one.

GA Can Learn from the Positives as well as the Negatives

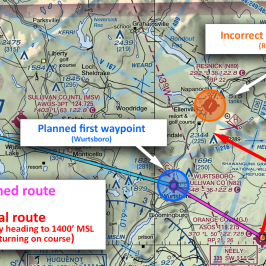

Not to put too fine a point on it, but if you strip this accident down to its basic structural components, there are a lot of similarities to the accidents we routinely see in GA. Lack of attention to aircraft performance; failing to meet a minimum performance standard; deviating from known standards or regulations; a failure to maintain situational awareness, and correctly prioritize tasks which present themselves in an airplane. In a nutshell, all of the advantages provided to a professional crew in terms of CRM training, aircraft specific training, and organizational rules designed to prevent accidents were consciously stripped away by terrible decision-making.

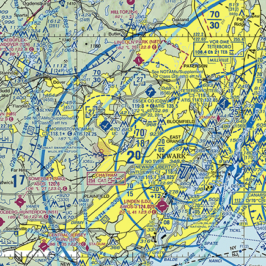

Equipment-wise, GA won’t ever match business aviation. We fly piston equipment, mostly with a single powerplant. Our flight decks aren’t as automated. We’re only just now starting to weed out the old vacuum pump-powered gyros for electronic replacements, a welcome trend which will certainly serve to save lives in the short and long term. But our equipment has gotten better. “ADS-B In” has made datalink weather and traffic common on the GA flight deck. Many single-engine airplanes are equipped with ballistic parachute systems. And we’re seeing lots of redundancy in the attitude presentations in the cockpit thanks to lower-cost AHRS offerings.

But most of our accidents aren’t caused by equipment. They’re caused by pilots. And saying “pilot error” is the cause of those accidents is really missing the point; why did the pilot make the same error that hundreds or thousands of pilots made before him or her?

Be a One-Person Flight Department

Last year, the Teterboro FAASTeam began encouraging pilots to train with their instructors at least one day per year rather than the 14 CFR 61.56 requirement to do so every two years. If professional crews train at least once per year (often it’s more — six months between recurrent training events) shouldn’t private pilots be willing to do at least a little more than the minimum? If only one day of training per year sounds low to you, it should… and hopefully that means you’re one of the conscientious pilots out there voluntarily choosing to go beyond the minimum standard.

Do you take part in designing your training? Good training is like exercise — challenging and, at times, downright difficult. The right training will focus on the areas in which you need the most help. Weaknesses can become strengths, but not without commitment to improvement and a humble self-assessment.

How’s your ADM and RM? If those terms sound foreign to you, meeting with an instructor and building some scenarios which test your Aeronautical Decision-Making and Risk Management could pay big dividends.

How about “organizational safety?” Does that sound like an overblown concept for a “one person flight department” who simply rents/owns an aircraft flown 100 hours per year or so? It shouldn’t. How do you maintain oversight of the airworthiness of your aircraft? Do you periodically review the logs when renting? Do you have an organized flight planning process which ensures you systematically review everything associated with the flight — weather, NOTAMs, aircraft performance? These are simple things to do in the grand scheme and only cost a few extra minutes here or there. But thinking about yourself as an operator rather than just as a pilot might be helpful; after all, there’s far more than goes into a safe flight than just starting up the airplane and pointing the spinner in the right direction.

“That’s too much work… this is supposed to be fun!”

Yes! I get that sometimes when I’m presenting on safety. And yes! It is supposed to be fun. So I say: isn’t it fun to feel relaxed and confident that your planning was thorough and that your flight fits your personal minimums? I certainly enjoy my personal flying quite a bit more that way. Too much work? It’s a few extra minutes baked into each flight; perhaps if a pilot is in too much of rush to spare those extra minutes, it’s not a good day to go flying.

In “Learjet Down” we looked at an accident which in some ways modeled behaviors which are more commonly found in GA accidents, with predictable results. If professional crews can find themselves behind the curve by disregarding the standards built to keep them safe, GA pilots are sure to see the same results if they follow suit.

Safe Flights!

-Ryan