Private Pilot Checkride Example

This is a true story, but I’ve changed some minor details to protect the innocent.

The applicant had completed the ground portion of his Private Pilot Practical Test in outstanding fashion, followed by a satisfactory preflight inspection of his Diamond DA-20. Suitably sweaty on a very warm summer day — it was pushing 35 degrees Celsius — we strapped in.

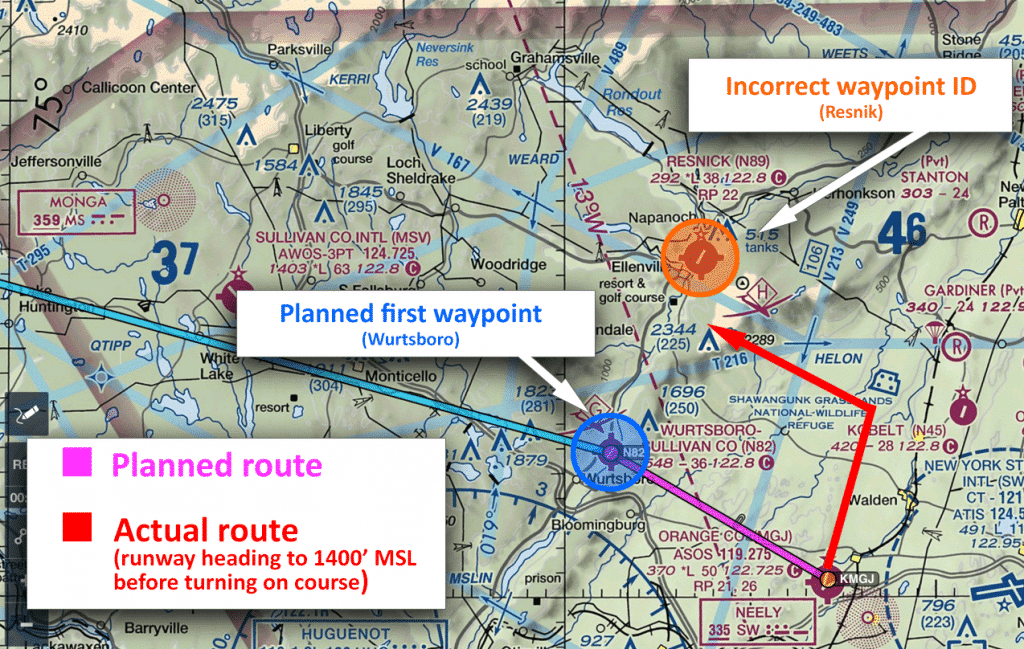

I reminded my applicant that our first objective was to complete Task VI. A., “Pilotage and Dead Reckoning.” His flight planning assignment was to fly from Orange County (MGJ) to Buffalo Niagara International (BUF) in New York. Why not? Niagara Falls in the summer is breathtaking! Too bad we wouldn’t actually be going there. His job was to use his pilotage and dead reckoning skills to navigate the aircraft to the first waypoint on his flight plan; he had selected Wurtsboro Sullivan County airport (N82). I had already briefed the applicant that I do not allow the use of GPS moving map displays for this task.

The applicant proceeded to provide a passenger briefing. He taxied out to runway 4 at Orange County (MGJ) and gave a thorough takeoff briefing which included his takeoff performance — bravo! “It’s a pretty long takeoff roll today,” he admitted.

Indeed it was. The diminutive DA-20, near its maximum gross weight of 1,600 lbs. with full fuel and the two of us aboard, accelerated sluggishly down the runway. Nonetheless, the performance was still adequate for the day VFR cross country flight which was planned. My applicant skillfully nursed the aircraft off the ground and held the proper airspeed for the aircraft configuration within a couple of knots.

If the aircraft was not exactly hot to trot on the takeoff roll, it was even less inclined to climb. The VSI indicated a climb rate of somewhere between 200-300 feet per minute.

After what seemed like an interminable few minutes, we finally reached 1,400 MSL – the altitude at which the applicant felt comfortable beginning his turn to the northwest. Right away, I noticed a problem: he was turning towards his pre-planned heading to reach his first waypoint. But that heading was predicated on a straight line drawn from the middle of the airport to N82… per his pre-flight planning.

We made the turn. The applicant began looking for Wurtsburo and in a few minutes, he identified its familiar runway layout — or so he thought.

Tricky; both airports have similar runway lengths and orientations. Both lie in a ravine which runs northeast and southwest. Both feature glider operations.

But it was Resnick he saw, and off the right side of the aircraft. Not Wurtsboro.

We can always learn, get better, and demonstrate our improved skills. A failure on this task on an FAA Practical Test is not the worst thing in the world. There’s something much worse.

The Accident on Superstition Mountain

This accident was a true tragedy. On November 23, 2011, a Rockwell International Aero Commander 690A impacted the western-facing rockface of the Superstition mountains on a night VFR flight. Aboard were six souls, three of them children. You can read the NTSB report here.

How could it happen? A highly capable aircraft, flown by an experienced pilot, with a lot of “skin in the game.” It was, as is so often the case with such accidents, a series of small transgressions and errors. Familiarity with the route. Complacency. Lack, or loss of, of situational awareness. A focus on mission success.

Six lives, cut short.

AOPA released an Accident Case Study via the Air Safety Institute. It’s worth watching.

The corollary between the two examples is starkly clear. The accident pilot was relaxed. It was a common route. The weather was good. The aircraft was capable. It was not within his mental landscape to consider that the aircraft might be aimed at CFIT from the first tower-assigned heading. The same was true of the private pilot applicant. He was so focused on flying his selected heading that he neglected to correlate the actual situation he was encountering in flight with his planning.

Accurate flight planning and pre-flight action is synonymous with safety.

That’s a strong statement and worthy of “heading” status. Indeed, it’s easy enough to let the electronic tools do the work for us. Given the boundaries within which they work, they are quite accurate. Quite precise. But can they maintain our SA for us? Can they cope with unexpected changes? That’s up to the pilot and that’s the reason this task is evaluated on the Private Pilot and Commercial Pilot practical tests. It’s also the reason I, and many other pilot examiners demand this task be accomplished without the aid of moving map displays.

Down the line from their encounter with the practical test, it’s a given that pilots will relax and begin relying on flight planning tools such as ForeFlight, Garmin Pilot, and others. What can’t be a given is the handing over of big picture SA (Situational Awareness) to devices. There is simply no excuse for the pilot being excluded from the decision-making loop based simply on the fact that he or she is using a device or application.

In both the Private Pilot checkride example and the accident involving the Aero Commander, the pilot made broad assumptions about the route during the pre-flight planning phase but did not adjust to the changing conditions of the flight itself. This is why the task is evaluated on the practical test.

And this is why precise and accurate flight planning is always at a premium, whether it be for a checkride or a routine night VFR flight. Had the private pilot applicant considered his DA-20’s climb performance — not just its takeoff roll — he’d have realized that it would take several miles to gain the altitude sufficient to make his on-course turn to the northwest.

Unfortunately, the pilot of the Aero Commander never had the opportunity to recognize his error or correct it.

Safe Flights!

-Ryan